By Tamim Amijee, Edna Chilimo and Elias Xavier

The role of funding in shaping local civil society organisations (CSOs) is significant. Considering that the bulk of funds for local CSOs in countries like Tanzania originates from donor countries, it is not surprising that those countries highly influence how the local CSOs have evolved and what they do. Too often, then, it seems to be only in name and people that some CSOs can be considered to be ‘local’. So is it possible to change this situation?

The three of us – all participants in the Consulting for Change programme funded by Nama Foundation and facilitated by INTRAC – recently contributed to a global webinar as part of International Civil Society Week 2017. This webinar, which explored partnership between local, national and international organisations and struggles related to resources, capacity, sustainability and accountability, raised many questions for us.

One of our concerns is that some parts of the ‘local’ CSO sector in the developing world have evolved as a copy of the CSO sector in the developed world. The funding, policies, activities, governance, and reporting are foreign. Even the local people in local offices of INGOs appear different from other working people and the community with their impressive buildings, car park full of imposing 4WDs, open plan office structures, free-flowing tea and coffee, imported furniture and smartly dressed people all appearing very busy.

Of course not all local CSOs and local offices of INGOs would fit the description, but many do. The reasons why this situation evolved are many, including: funding sources, partnership models, INGO and donor perspectives on development, and individual interests of expatriate staff and local individuals.

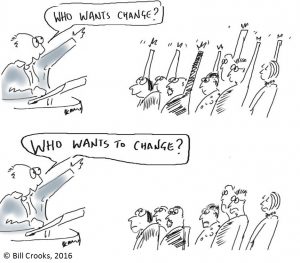

Assuming that there is a desire to change the situation, and that true local CSOs have value, we must then ask ourselves how can we change? What needs to happen to make local CSOs truly local?

Clearly, there is a need for some very critical soul-searching and reflection in the CSO sector, both within the developing world and within funders and supporters in the developed world. The CSO sector needs to ask why any local CSO is established, who started it, what it is doing, whom it is really serving, whether there are any masters, if beneficiaries really feel their needs are addressed, who really decides the plans and activities, who is actually answerable to whom, if the CSO is sustainable, does it have the institutional structures for independent longer term survival, etc. etc.

Among the many things that need reflection and reassessment, funding, we believe, is a significant issue. Funds determine survivability, and recipients know too well that without funds, it may mean their end. Yet funds can be to influence recipient agendas. In order for CSOs to think freely, independently and work out their own priorities based on the actual needs of the communities they serve, the dependency cycle on funds from foreign sources/the developed world has to be broken.

Raising funds locally for local community and social needs is widespread, at least in the East African region. Large sums can be raised for weddings, funerals and other community projects, from family, friends, work colleagues and the community. Often, popular and influential persons are used as fundraisers. Other funds are raised through corporate sponsorships, and yet more is raised through methods such as raffles, dinner, walks, auctions, and donations. A local charity club in Dar es Salaam has raised large sums for assisting the children’s cancer ward at the national hospital. Another similar club regularly raises about $10,000 to pay for free 2-3 days’ eye cataract clinics throughout Tanzania. In 2017, this club has held five eye clinics, examining over 1,000 patients and operating about 150 cataracts per clinic.

Could we apply learning on this sort of fundraising to other development projects in Tanzania? Would it be possible, for example, to make local CSOs source all their funding needs locally? We know this sounds next to impossible in the present times where the annual budgets of many local NGOs hover in stratospheric levels of millions of dollars. In Tanzania, it is not uncommon for some local NGOs and CSOs to receive more than USD 1 million p.a. from donors and INGOs.

How would it be possible to bring about such transformation? Could donors and INGOs dramatically reduce the funding they make available to local CSOs? Are local CSOs that have long relied on external funding courageous enough to break loose from external donor purse strings and swim in uncharted waters? Would local CSOs limit their activities to only the amount of funds they are able to raise locally? Can local CSOs embark on sustainable investments that would provide income streams to fund their activities?

In Tanzania there seems to be a big appetite for more creative approaches among CSOs, and there is enormous social capital to build on. As consultants and capacity builders we want to support local CSOs and help them think differently about their funding, accountability and relationships. The Consultants for Change programme has helped us to do some critical soul-searching and reflection on ourselves. We need to make sure that what we offer learns from but is not dependent on external funding models or ideas. We need to listen to our clients to build trust and credibility. That way we hope to help CSOs in Tanzania through a process of profound change to become truly local.

About the authors:

Edna Chilimo is Capacity Development Manager at the Foundation for Civil Society in Tanzania

Elias Xavier is an independent consultant in Tanzania

Tamim Amijee is an independent consultant in Tanzania