By Nigel Simister

As I explored in the previous blogs, M&E needs to change to better support adaptive management. This is already well covered in development literature and debates, but based on my own experiences and opinions, deeper and sustained shifts are necessary to truly embrace adaptive management.

Firstly, adaptive management may require a lowering of barriers between formerly discrete processes. In simple projects and programmes the divisions between planning, monitoring, review, evaluation and research may be relatively clear. But adaptive management requires programmes to approach problems from another angle; first deciding what type of information is needed and then designing a suitable process.

For example, a programme team might discover that some groups of stakeholders are failing to benefit from a programme intervention. It might decide as a result to develop some purposefully sampled case studies, and then conduct cross-case analysis to find out why they are not benefitting. To do this it will need to decide on issues such as whether to use internal or external staff, how much money and time to spend, what questions to address, what tools to use, and how to feed the findings into decision-making. Whether this exercise is called impact monitoring, evaluation, review, research or simply ‘a study’ becomes almost irrelevant. Once a certain level of complexity has been reached the terms tend to lose their meaning. Each exercise is different, and each will need to be designed accordingly.

More internal and less external evaluation

This may have major implications for how evaluations on adaptive programmes are conducted in the future. There may need to be:

- very short and focused studies, rapidly designed to achieve specific objectives;

- long-term relationships between evaluators and programme teams; and

- more internal (or mixed) teams that can provide many of the functions of evaluation, but on an ongoing and flexible basis.

This means that NGOs pursuing adaptive management will need to recruit, manage and nurture talent within internal teams to support their capacity to handle M&E and learning within complex programmes without so much reliance on external expertise.

The other side of the coin is that adaptive programmes are often simply too complex to evaluate by people who have not been involved. Staff managing complex programmes often complain that they spend a vast amount of time either getting evaluators up to speed, or spoon-feeding them information in the hope that this information will later make its way into evaluation reports.

Formal evaluations, especially for accountability, might need to be re-designed. For example, it may become common practice for internal M&E (or MEL) teams to lead evaluations, with external evaluators acting as sounding boards and providing quality assurance. Or the job of the external evaluator may be less to provide an objective assessment of change, and more to hold internal MEL staff to account for the quality of their work throughout a programme.

In any event, the evaluation community will need to make some changes. But it is a powerful community with a vested interest in the status quo, and change will not come without some opposition.

Appreciating uncertainty

An enhanced appreciation of uncertainty may also be necessary. Linear planning tools such as the logical framework, and approaches such as Results Based Management (RBM), have encouraged a ‘black and white’ assessment of change to ensure reporting against milestones and targets.

However, at outcome and impact level many, if not most, M&E findings come with some level of uncertainty. This is not so important when using M&E solely for accountability purposes. But if NGOs wish to take management decisions based on M&E information they need to know what level of uncertainty is acceptable. Is it acceptable to make a timely management decision based on information that is ‘likely’ to be accurate? Or should an NGO spend more time and resources to increase the certainty of findings, with the danger that course corrections might be too late? This is a challenge that comes up constantly in INTRAC training courses, particularly from people operating within humanitarian programmes.

We can learn something from physical scientists here: “estimating the uncertainty on a result is often as important as the result itself. It is only when we are aware of our ignorance that we can judge best how to use knowledge. In engineering or medical science, a deep understanding of uncertainty can be a matter of life or death. In politics, over-confidence is often the norm; uncertainty is seen as weakness when really it is a vital part of decision-making” (Cox and Forshaw 2016). [For politics substitute evaluation].

If M&E findings begin to matter more – in other words if they result in real strategic changes affecting real lives – it will become more important both to ensure that findings are as precise as possible and to recognise the uncertainties. M&E staff will need to get used to presenting information with a full explanation of caveats, reporting not only findings but also the limits of those findings, and the implications for decision-making.

Balancing time, resources and evidence

It will often simply not be possible to wait until all the facts have been fully analysed before making decisions. So a constant balance will be necessary between rigorous evidence and timely evidence (Valters and Whitty 2017). Staff will have to assess what type of study can be achieved with a given set of resources in a specified time.

This, too, flies in the face of the current tide, as more and more attention has focused recently on the ‘rigour’ of evaluations in demonstrating results rather than the utility in supporting decision-making.

Accepting varying credibility and reliability of evidence

Finally, complex programmes are often broken down into smaller units (such as projects), implemented through different operational partners or by networks and coalitions. Information tends to be collected and analysed by different people and organisations for tactical adaptation, and then analysed again at strategic programme level. The task of the strategic analysis is therefore to make sense of data that has been collected and analysed in different ways at different times and in different locations, and to come up with conclusions and recommendations that are useful. Inevitably, the information will be of varying credibility and reliability.

Such challenges are regularly faced by M&E staff working within the head offices of NGOs – called ‘infomediaries’ by Ruff and Olsen (2016). Unfortunately, there is very little support currently available to help them. Some guidelines would be a useful start.

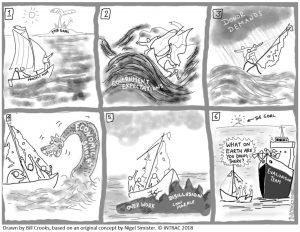

Overall, INTRAC is supportive of the drive towards adaptive management and feels it is long overdue. But its pursuit will require deep and sustained shifts in thinking, capacities and working patterns – not just within NGOs, but in the wider system as well. Nobody should underestimate the difficulties of bringing about these shifts.

As with all profound shifts, there will be losers as well as winners. But if we as NGOs get it right, the winners will be the primary stakeholders we are mandated to support. Having to change deeply ingrained working patterns should not be too high a price to pay.

References

Cox, B and Forshaw, J (2016). Universal: A guide to the Cosmos. Allen Lane, Penguin, Random House, UK.

Ruff, K and Olsen S (2016). The Next Frontier in Social Impact Measurement Isn’t Measurement at All. Stanford Social Innovation Review.

Valters, C and Whitty, B (2017). How to manage for results in DFID. Briefing Note, 3rd November, 2017.