By Hiwot Alemayehu and Rick James

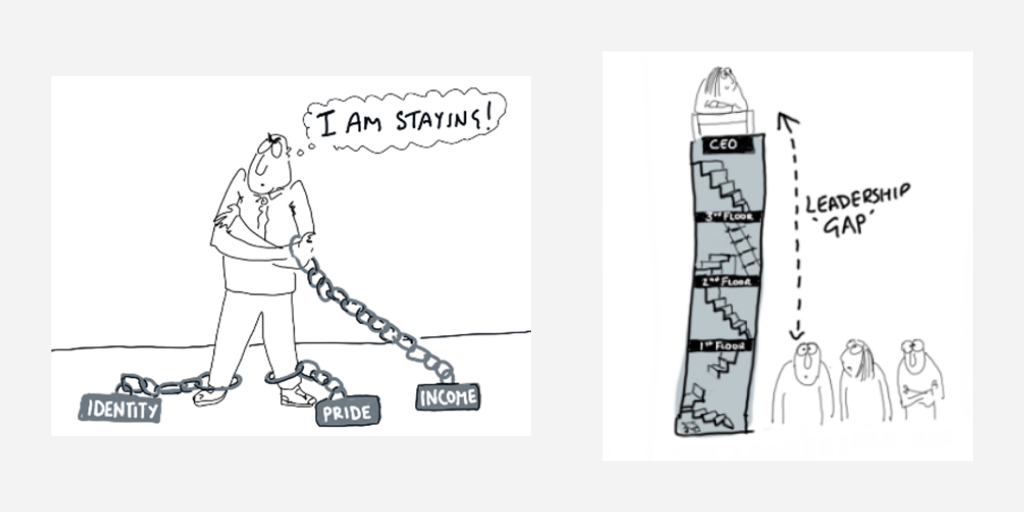

The NGO sector in Ethiopia is now “gripped by founder syndrome” according to research undertaken in 2021. The research found that the board, the leader and the senior staff are the most important actors. But funders too have a critical role to play in supporting healthy leadership transition. The Ethiopian civil society leaders interviewed in ‘Supporting CSO Leadership Succession’ asked funders to address the issue in four key ways, by:

- engaging more directly with grantee governance and second-line leadership;

- putting succession more explicitly on partners’ agendas;

- providing targeted capacity strengthening support; and

- taking a longer-term, more strategic approach to funding.

20 semi-structured interviews conducted in Amharic with Ethiopian civil society leaders and government representatives formed the bulk of the data gathering. It also built on prior INTRAC research and publications in this field. The research identified the leader themselves, the board and the senior staff as the key players in founder transition. The cultural and political context also has an important influence. Funders too have an opportunity to help or hinder the process.

Sadly, the research found little evidence of any meaningful funder engagement with the issue of founder succession in Ethiopia to date. One respondent stated that “Donors have not played any role in supporting our transition.” One or two mentioned that some US funders like “ask about leadership transition during their institutional capacity assessment” but then never follow through nor ask these questions again. Respondents only recalled one training that had focused on leadership succession, but this took place more than 10 years ago!

Instead, the research found that the ways many funders have operated in Ethiopia has exacerbated the challenge of transition. Short-term project funding tends to ignore the organisation’s health. One respondent said that “if donors only fund a project, they do not really assess governance or leadership succession issues.”Another observed that “donors are not long term thinkers. They might fund a project for many years, yet lack the commitment to long-term sustainability.” Previous government constraints on external funding in Ethiopia have obviously influenced this approach, but now the law has changed and restrictions eased.

Respondents also observed that funders often pay too much attention to individual leader. As one put it: “Funders are festering the problem by establishing trust with one person, usually the CEO, and demanding the presence of that person at all times. This perpetuates malpractice in the organisation.”

Instead, Ethiopian leaders in this research asked funders to get more involved in the sensitive topic of leadership succession. They recommended four practical ways to do this.

1) Pay greater attention to governance and second-line leadership in making funding decisions and then in monitoring the grant management.

The research showed the key role that boards play in ensuring healthy succession. Consequently, respondents said that “funding should be tied to internal governance requirements”. They asked funders to engage more directly and consistently with partners’ boards throughout the relationship (easier now that online board meetings have become more normal).

Respondents also felt funders could do more to engage with senior managers or potential leaders, not just the CEO. One respondent said: “Show you have faith and are not centralising leadership in your mind too. Give space to growth from inside.” One went further to suggest that funders make it a condition for grantees to bring on the next generation of leaders from the start of the grant, not as an afterthought at the end.

2) Put succession on partners’ agendas.

Although it is an acutely sensitive issue, Ethiopian respondents felt that “donors raising the awareness of leadership succession is vital”. They feel that funders had a critical role in raising difficult and uncomfortable questions, saying that “donors can ask the right questions in the right time for leaders (and boards) to pause and think through their leadership and show more commitment to sustainability”. Because of their distance, funders are able to ‘ask the unaskable’ – thereby legitimating discussion of an otherwise taboo topic. Many respondents felt that funders should explicitly ask to see a succession plan.

3) Invest in capacity strengthening.

Respondents suggested a number of ways to do this:

- Putting together resources for sharing good experiences of transitions.

- Supporting leadership coaches or peer learning sets to help founders discuss succession in safe, supportive environments.

- Encouraging specific training for all boards because “if boards are not functioning you cannot have healthy succession”.

- Supporting programmes for emerging leaders.

4) Fund more strategically.

These initiatives need reinforcing with core funding to encourage longer-term strategic thinking. They may also need to cover ‘difficult’ (but essential) areas of second-line leadership and the costs of founder transition. As one said: “One-person leadership is always easier for decision-making, but shared leadership is one way of making transition easier.” Others said the funders could play a key role in supporting transition costs, creating a paid space for exiting founders to reflect and document their learning.

Healthy leadership transition is key for resilient, sustainable organisations. Rather than shy away from this sensitive and complex challenge, Ethiopian civil society leaders are asking funders to start supporting succession more intentionally. They offer realistic and practical ways to do this well.