By Rod MacLeod

This blog is a product of research on core grants commissioned by the Laudes Foundation. This is a topic that has been rising up the agenda and Laudes Foundation has increasingly been using this funding mechanism itself. The aim of the research was to learn lessons from the provision of core grants in the wider sector. It involved a literature review and interviews with donors, recipients and observers of the sector, as well as the author’s own experience as a practitioner and a consultant. The full paper can be accessed here.

Blogs in this series:

No. 1: Core grants: Why isn’t everyone using them?

No. 2: How to select suitable recipients of core grants

No. 3: How to use a core grant

No. 4: How to measure the impact of core grants

The paradox of core grants [1] is that, while many donors appreciate them in principle, they do not always put these sentiments into practice. What explains this anomaly? There are a number of reasons, but one of the most significant is the challenge of measuring their impact.

In fact, there are multiple challenges. If a grant covers the whole of an organisation, it is not even possible to state precisely what activities and outputs it has funded. It might have been that high profile advocacy campaign, but equally it might have been the rather less attractive administrative costs.

At the outcome level, if an organisation is working in multiple areas, aggregation and summarisation is complicated. Even where an organisation has had a clear impact, assessing the contribution (let alone attribution) to a donor core grant is hard.

When donor boards or public accounts committees ask, ‘What exactly has our investment achieved?’, there is therefore usually no simple, clear-cut answer. Nevertheless, this issue will need to be addressed in some way, so how best to approach it?

Being clear on objectives

As with any M&E system, being clear on the objectives for why the impact of core grants need to be measure is essential. Typically, accountability and learning/improvement are the top priorities, but the balance between them varies. For government donors, there is usually pressure to demonstrate results to satisfy public accounts committees and political masters. For other donors such as trusts and foundations, there is often more leeway, as predominantly they can focus more on satisfying their own boards.

Different approaches

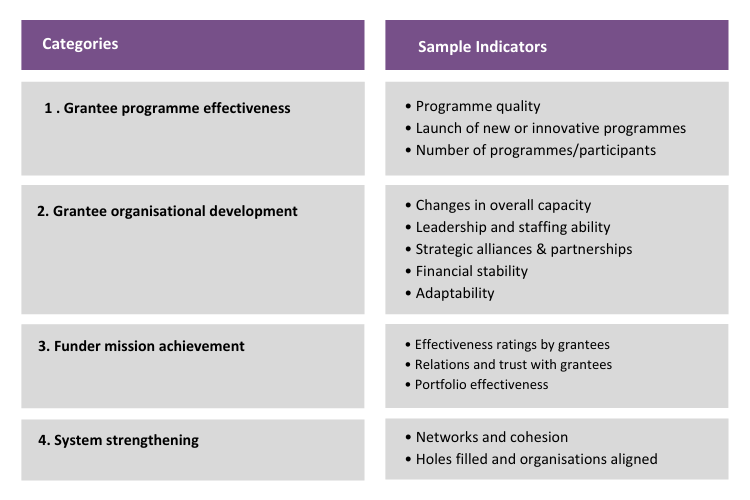

These different circumstances affect how different donors set out their M&E requirements. Some government donors have progressively required more specific results frameworks, which moves core grant closer to programme grants, thereby undermining the potential advantages of unrestricted funding. Trusts and foundations have a greater freedom with respect to their M&E systems and respond in a variety of ways. TCC (The Conservation Company) Group sets out a comprehensive framework for assessing core grants, which is shown in an adapted form as follows:

But this framework still leaves open the question of how to develop and measure indicators, particularly at the programme effectiveness level. This will depend on the nature of the work. For some focus areas, such as supporting small businesses, there are some clear-cut metrics, such as revenue, cash flow, profitability, jobs created and sustainable livelihoods. For others, advocacy work or capacity development, for example, this is more challenging.

Carol Chandler of Northern Rock Foundation argues, ‘The obsession with counting and numbers and not trusting the organisation to be able to deliver is based on a lack of trust and need for control on the part of funders.’ Power imbalance can lead to what Melinda Tuan called a ‘dance of deceit’ with the grantee pretending to meet the donor’s requirements and the donor pretending to believe them. A ‘rubrics’ approach provides a more qualitative way of assessing the progress of an organisation rather than relying on Key Performance Indicators (KPIs).

But an alternative approach is simply to pose a number of open-ended questions such as:

- How do you see the context changing?

- How are you using the money? Did you consider other things?

- How have you changed as an organisation?

- How do you take decisions?

- How do you learn and adapt?

The emphasis here is more on understanding the organisation itself and examining whether it is actively thinking about these questions, learning and adapting, rather than trying to pin down its programmatic outcomes, which is often an elusive and fruitless task.

If donors really believe in the merits of core grants (stability, flexibility, innovation, supporting OD, changing the nature of the donor-grantee relationship etc.) and trust their own selection processes, then taking a broader and less controlling approach to measuring impact makes sense. This is in keeping with the increasingly popular concept of ‘trust-based philanthropy’ amongst more progressive donors.

[1] By ‘core grants’, we are discussing donor funding with a high degree of flexibility, which can be used to cover organisational development work and the administrative running costs of the organisation, as well as programmatic work.