By Sarah Lewis and Rachel Hayman.

NGOs have not been good at designing or implementing exit strategies, and have been notoriously weak at sharing their experiences with others. The Action Learning Set (ALS) was formed in March 2014 in response to this problem.

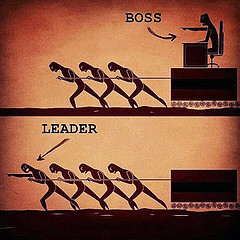

During our meetings, we repeatedly came up against the need for appropriate direction from senior staff and strong leadership as critical points in the exit process. Again and again, we found our discussions revolving around the need for investment in the exit process, investment of both staff time and financial resources. Without senior buy-in, such investments will not happen. This begs the question of whether poor leadership around exit may be one of the causes of the problem the ALS set out to address.

So what difference and impact do supportive leadership make in exit processes? Does a lack of leadership cause particular problems in certain stages or aspects of exit? And what level of engagement should senior managers have after the decision to exit has been made?

These questions were brought to the fore at the March 2015 meeting of the Action Learning Set on Exit Strategies, where senior managers and staff at different levels were invited to join the regular group of participants to debate the issue of leadership during exit from programmes, projects, and partnerships.

Here are a few lessons emerging from our meetings around leadership:

1. Communicating with those heading for the ‘departure lounge’

Leaders are the ones who make the all-important decision to exit because the job is done, the strategy has changed, or finances are squeezed. Communication with partners, staff in country offices or programmes, and those who will manage exit, is crucial. This might include:

Leaders are the ones who make the all-important decision to exit because the job is done, the strategy has changed, or finances are squeezed. Communication with partners, staff in country offices or programmes, and those who will manage exit, is crucial. This might include:

Undertaking a consultation process before the final decision to exit, if appropriate

- Providing a clear, consistent rationale and consulting on how the process will take place at the decision to exit

- Updating those affected on progress between the decision point and the moment of exit

Timely communication can help staff at all levels to align themselves with the process and help to implement the exit smoothly. This will help ensure that professional relationships and organisational reputations are not damaged. As one participating organisation put it, “there is always a chance that you will see your partner at a party in the future”.

Overall, and arguably most importantly, strong and appropriate communication shows respect for those affected by exit, respect for staff and partners, respect for the work that has been done, and respect for communities or beneficiaries in areas where interventions are coming to an end.

2. Supporting staff during the exit process

Beyond providing financial resources to support the process, leaders need to give their time, status and thinking to those responsible for carrying out exits. This links back to our earlier discussion on staff care and personnel during exits, and reinforces the importance of providing support for managers implementing exit so that they feel recognised, guided and motivated. If staff do not feel supported or incentivised to stay, the organisation risks losing them before the end of the process, with negative implications for continuity and learning. As one participant observed, leadership also starts with each individual staff member feeling responsible for the process.

Suggestions for support include:

- Increasing contact points and checking in with staff at key moments in the process

- Facilitating peer-to-peer support. For example, EveryChild’s India and Malawi Country Directors visited one another to exchange their experiences during the closure of their offices as part of planned exits

- Ensure that those responsible for exits do not feel isolated

- Have a positive mindset, see exit as an achievement not a failure, be motivated, champion decisions, and lead by example

It is essential that leaders find the most appropriate way to provide support at the right times, in a way that is proportional and considered. Our discussions highlighted the need to balance being flexible, such as extending the timeframe for exit when appropriate; while being directive, including pushing back to see through exits as planned.

3. Embedding learning on exit into organisational systems and practice

The exit processes that the participating organisations in the ALS came together to share have all been rooted in strategic decisions to reshape, reframe or realign priorities and programmes. A huge amount of knowledge about the exit process and ideas for what could be done differently next time is built up by the individuals and teams involved. But there is a risk that this learning gets lost or disappears altogether if the team are too insular, key people move on, or the entire process is not seen as an important investment.

Ways to embed learning include:

- Make sure that exit is built into the next programming cycle and organisational strategy, not in a tokenistic way but seriously, building on the wealth of learning available. If it is clear from the outset when and how exit might happen – with a written record that changing teams can refer back to – then the exit should be expected and easier when it happens

- Build monitoring of, planning for and learning about exits into mid-term and strategy reviews

- Ensure the team carrying out exit are sharing their experiences widely and continually, for example by integrating them into different teams at key moments

- Recognise that a responsible exit is an important investment, and allocate resources for the time to stop, reflect, evaluate and learn

All of the above needs to be supported and driven by senior staff and leaders. If this does not happen, organisations are at risk of repeating mistakes or reinventing the wheel, rather than building on best practice. We know that exit is hard to do well, but as one Action Learning Set participant said, “Given the challenges and potentially painful experience of exit, it is worth learning to do it well”.

Final thoughts

Over the past year, we have observed real changes in the participating organisations’ approaches to exit; concrete action has been taken by many participants based on their learning. Their leadership have supported this individual and organisational learning by allocating time and resources to the Action Learning Set. The group opened themselves up to scrutiny and challenged one another due to their common desire to do exit better in the future. The critical test for all the participating organisations will be in embedding that learning into organisational systems and practice, not just at this moment in time, but into the next strategic plan or major programme cycle.

Organisations need to look at the space they provide for learning on exit. This is something that happens continually in the life-cycle of organisations, not just in the wake of a financial crisis or major strategic review. Leadership engagement is important at many levels and at different points in the process. Its absence can have negative consequences on the communities and partners that are ‘left behind’, the legacy of the work of the exiting organisation, and its reputation.

We know that there are many organisations facing the same challenges every day, looking for guidance and support. If exit is to be done responsibly and well, then leaders have not only to buy into the process, but to lead by example.

The Action Learning Set on Exit Strategies includes British Red Cross, EveryChild, Oxfam GB, Sightsavers and WWF-UK. Facilitated by INTRAC, it ran from March 2014 – March 2015.

We used the term ‘leadership’ broadly to cover key decision-makers in organisations. This includes CEOs, Senior Management, Boards/Trustees, Regional Management or Country Directors.

Image credit: ‘Leadership vs. management’ by Olivier Carré-Delisle via Flickr. Used under Creative Commons licensing.